After attending a conference called The Makers Summit a couple of weeks back where I saw two founders talk about “10x” products, I figured there must be experts who have looked for patterns in how they emerge and written about them? And sure enough, as I started reading, I discovered there is a market phenomenon called “Disruptive Innovation” which often provides a 10x experience for the right customers when a recent technological advance is applied to fulfil their needs. It also struck me that though I was reading two different sets of people, there was significant overlap between their ideas and they were both arriving at the same 10x experiences but from different starting points.

The two sources I looked at are:

i) The writings of people affiliated with YCombinator, namely Paul Graham and Peter Thiel

ii) The process of “Disruptive Innovation” as explained by the late Harvard Professor Clayton Christensen

Venture Capital

Imagine you are living in a developed country with stable and free political, economic systems. Where would you expect a 10x improvement in the average consumer’s lifestyle to come from within the next few years? In a developed country most market needs are already being met in some form or the other, and you need to be an industry insider to be aware of upcoming needs within a specific niche. If you happen to be a venture capitalist, you need to find a source that can do this not once but repeatedly!

Therefore it is not surprising that venture capitalists reach for technological improvements as a driver for creating dramatically better customer experiences. In any country, its scientific and technical workforce will be continuously pushing the boundaries of their fields through ongoing work. Now it’s up to the tech-savvy entrepreneur to identify where one of these advances – even if incremental compared to its predecessor – can be a game changer when applied to a specific customer problem. For example, it could be that network bandwidth has improved just enough to support video streaming, or mobile phones got faster just enough to run some machine learning workloads locally.

It is critical to note that the 10x feeling is in the minds of the users, and not with respect to either the technology or the entrepreneur. This emphasis on the user was driven home to me last week as I read through the hundreds of responses to my question on Hacker News: What are some 10x software product innovations you have experienced?

Paul Graham’s writings presuppose all this background, which allows him to be clear and direct in his advice to entrepreneurs. In his famous essay “How to get startup ideas“, he suggests that you must get to the leading edge of a field – at least as a power user if not as creator – and then, to quote his own phrase, “Live in the future, then build what’s missing”.

Peter Thiel has good advice on the “build what’s missing” part in his book “Zero to One – Notes on Start Ups“. Among the criteria he suggests is the 10x rule: You need to be 10x better than your competition. This will not only make it hard for competitors to catch up, but also overcome any hurdles customers face when adopting your product. But then Thiel proceeds to set an impossibly high bar. He says you should rely on some kind of proprietary technical advantage that can’t be replicated. This is easier said than done, given you are a puny startup! Even Thiel’s own examples don’t back up his advice: Amazon at its beginnings was no match for offline bookstores, but bookstores are not exactly known for being tech savvy. And while Paypal may have made it 10x easier to sell on eBay, by no means was it threatening any big financial institution at the time.

Disruptive Innovation

Clayton Christensen and his group at Harvard, on the other hand, assert explicitly that a new firm can provide 10x experiences on the back of recent technological breakthroughs; only it’s more likely to be at the lower end of the spectrum of existing users of some product. This includes customers who feel they are paying too much for the handful of features they use, or people who have chosen not to use it because of price, complexity or lack of access. Intuitively this makes sense: any new piece of technology will have warts, and it’s best not to go after the most sophisticated users at this stage. Christensen further analyzes how the traditional incumbents in the market may react to this new firm that caters to the low end, why they usually don’t succeed and so on. It is this entire chain of events that he terms Disruptive Innovation. Armed with this lens, our tech-savvy entrepreneur can conclude that while the job is still to match up a recent technological advance with a game-changing customer experience, he or she will do well to focus on the lower end of a spectrum of users.

Similar to how Graham’s extreme example of an unfulfilled market need is your own need, Christensen’s extreme example of a low end user is someone who is not using a product at all – the so-called “Non-Consumption” case. When you genuinely enable non-consumers to get the benefits of a product, the improvement they feel could be much greater than 10x! Moreover, it is easy for existing companies to overlook non-consumers because they lie outside their customer base and typical segments or demographic profiles. But how does an entrepreneur locate them? There is no easy answer to that either, but I can point you to one episode of a podcast series called Disruptive Voice run by Christensen’s team: How to spot Non-Consumption? To clarify some of the terminology you will see there: people “hire” a product for a “Job to be Done”. They have “Struggling Moments” either while using the product or before it, and it may finally end in Non-Consumption. In Graham’s advice the entrepreneur himself is the one going through this cycle.

In a developing country like India, non-consumption is likely pervasive in technology enabled products! People are always opting out because of price, lack of bandwidth, complexity of the product, unfamiliar language etc. In the recent conference The Makers Summit run by Inc42, quite a few sessions were dedicated to overcoming such hurdles in the country.

Synthesis

Coming back to the YCombinator strand, Graham does touch upon the low end consumer in that Startup Ideas essay when he asks, “Are there groups of scruffy but sophisticated users like the early microcomputer ‘hobbyists’ that are currently being ignored by the big players?”

The phrase “scruffy but sophisticated” is doing a lot of work there, and in fact links to another essay called The Power of the Marginal. But what is relevant here is the word “sophisticated” which connotes a customer who can pay. When turning the lens on non-consumption or the low-end, keep in mind a big challenge such products face: the lack of a willingness to pay!

Traditional Metrics

While ideas like 10x, technological breakthrough, disruption and non-consumption may appear exciting, ultimately these are just tools – a means to the end of creating something people will pay for and sustains you and your company. So even a product developed using these concepts should have satisfactory answers for questions that are asked of all products. For this I found the set of questions created by Product Positioning expert April Dunford to be useful. Here is a company called Userlist using her playbook: How We Used April Dunford’s 10-Step Method to Overhaul Positioning at Userlist.

Why undertake this exercise sooner than later? It is because Dunford claims that positioning informs a product’s features and how you package and market it. But if your product relies on a recent technical breakthrough or wizardry it might make sense to wait a bit until you actually have something working before going through this exercise. Referencing Graham’s marginal essay again, he suggests “just try hacking something together” and be completely ok with it if you fail. An attempt at a 10x product improvement at the low end via the application of a recent technological advance constitutes a genuine circumstance for a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). You are not even looking for any particular combination of features that a customer will like, but just whether a product can at all be built to fill an already existing gap.

Conclusion

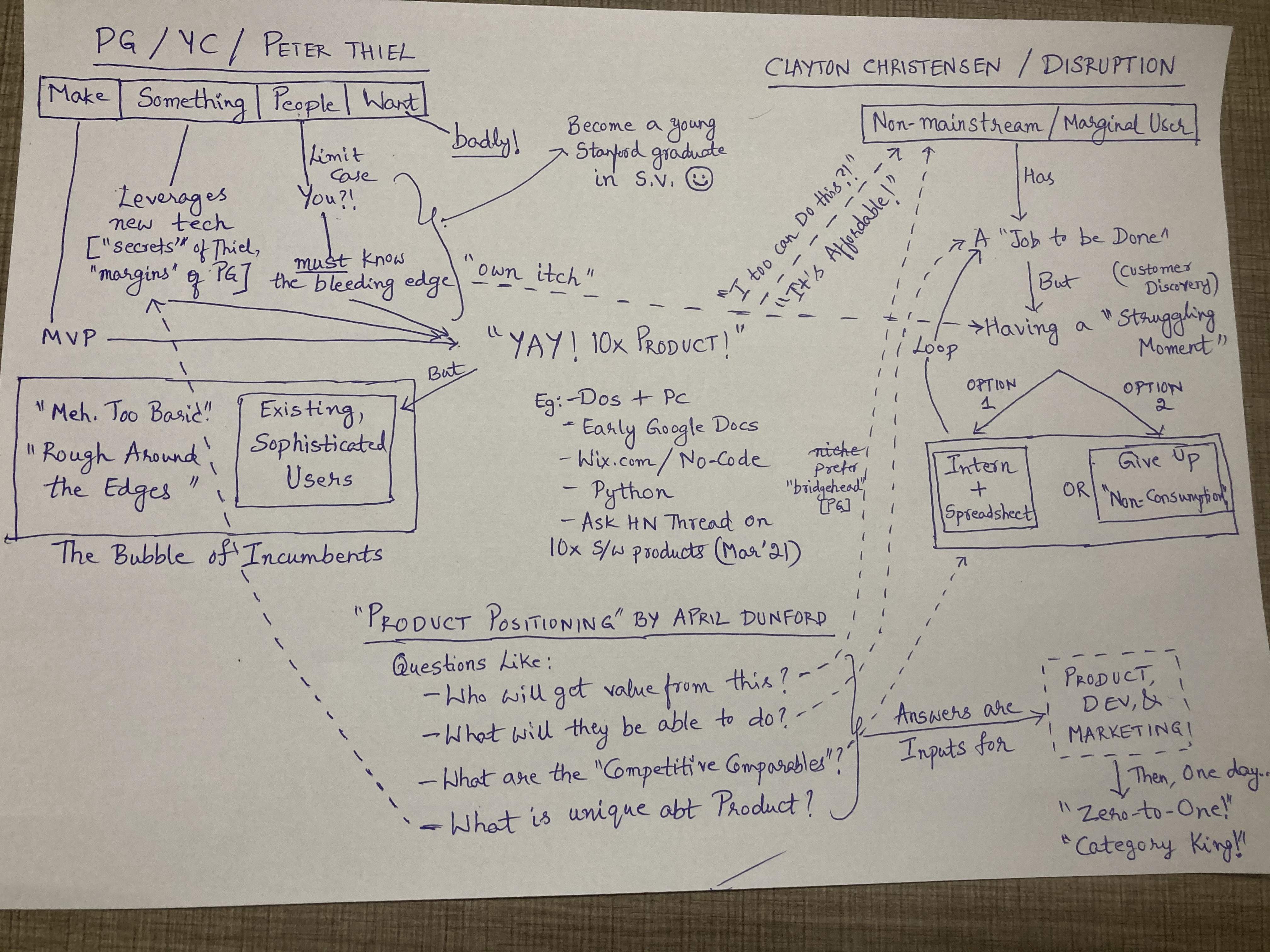

As I read through all this material and started noticing the connections, I thought of bringing them together into a single diagram, or cheatsheet if you will. You can find that image below. The figure may look daunting at first, but if you have read this article thus far, you will see that it just lists the components of our three main topics (the YCombinator strand, Disruptive Innovation and Product Positioning) and shows their connections. Remember that one person’s “just good enough” can be another person’s 10x! 🙂